Showing

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/TheAlternativeCourse.cls 87 additions, 0 deletions...console_toolkit/source/exercises/TheAlternativeCourse.cls

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/CC-BY-SA_icon.pdf 3 additions, 0 deletions...console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/CC-BY-SA_icon.pdf

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/CC-BY-SA_icon.svg 3 additions, 0 deletions...console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/CC-BY-SA_icon.svg

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/TheAlt_original.svg 3 additions, 0 deletions...nsole_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/TheAlt_original.svg

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/logo.png 3 additions, 0 deletions..._archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/assets/logo.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/exercises.tex 804 additions, 0 deletions...tk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/exercises.tex

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/img/Light_Bulb_or_Idea_Flat_Icon_Vector.svg 3 additions, 0 deletions...rce/exercises/img/Light_Bulb_or_Idea_Flat_Icon_Vector.svg

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/img/light_bulb.pdf 3 additions, 0 deletions...chive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/img/light_bulb.pdf

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/img/regex_golf.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...chive/console_toolkit/source/exercises/img/regex_golf.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/Makefile 25 additions, 0 deletionsarchive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/Makefile

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/GullBraceLeft.svg 3 additions, 0 deletions...chive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/GullBraceLeft.svg

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/borg_logo.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...k_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/borg_logo.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/cl.png 3 additions, 0 deletionsarchive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/cl.png

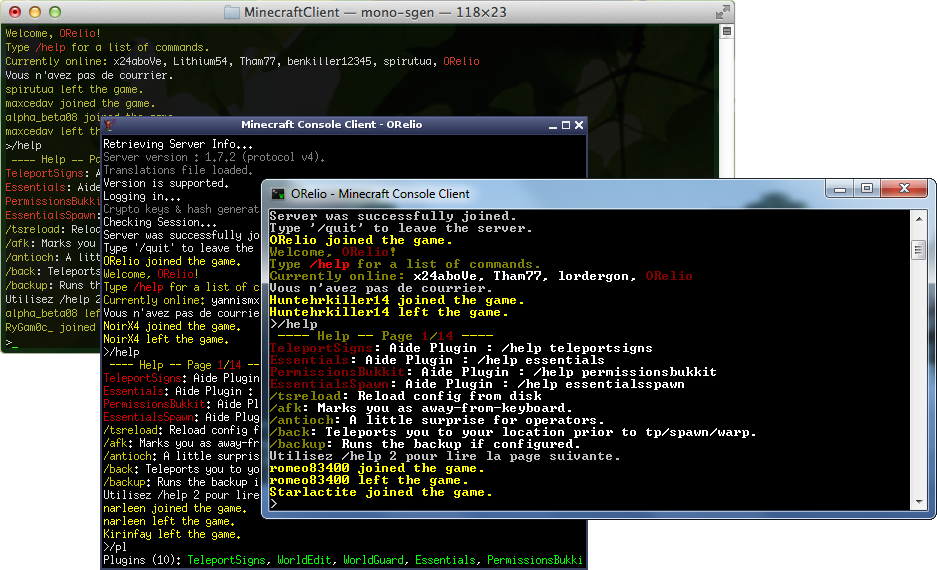

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/consoles.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...tk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/consoles.png

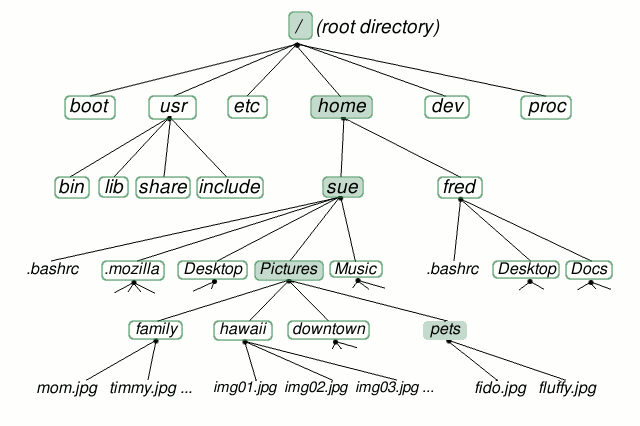

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/dirtree.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/dirtree.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/fs.png 3 additions, 0 deletionsarchive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/fs.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/fsf.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...ive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/fsf.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/git_branches.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...rchive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/git_branches.png

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/git_logo.png 3 additions, 0 deletions...tk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/git_logo.png

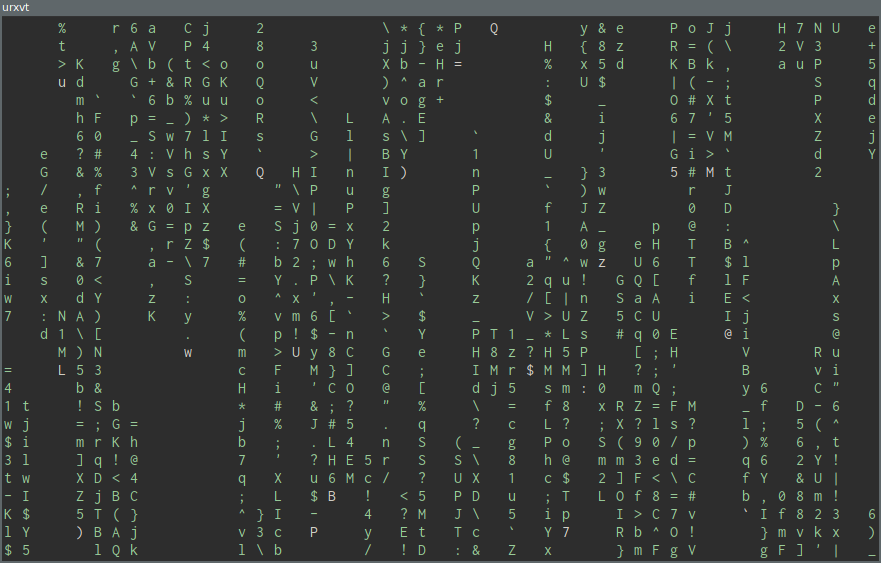

- archive/ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/matrix.png 3 additions, 0 deletions.../ctk_archive/console_toolkit/source/slides/img/matrix.png

File added

source diff could not be displayed: it is stored in LFS. Options to address this: view the blob.

source diff could not be displayed: it is stored in LFS. Options to address this: view the blob.

130 B

source diff could not be displayed: it is stored in LFS. Options to address this: view the blob.

File added

130 B

source diff could not be displayed: it is stored in LFS. Options to address this: view the blob.

130 B

130 B

131 B

130 B

131 B

130 B

130 B

130 B

131 B